Paperclips

In 2003, the philosopher Nick Bostrom argued that artificial intelligence might become dangerous even if it wasn’t designed with malicious intent.[1] He offered a thought experiment to illustrate the point. Imagine, he said, that we design an AI to manufacture paperclips. If that AI becomes powerful enough, it could start “transforming first all of earth and then increasing portions of space into paperclip manufacturing facilities.”

In today’s debates about AI policy, the worry that Bostrom identified is called the AI alignment problem. We might design an AI with a goal that isn’t fully aligned with our values, and that misalignment might cause harm. It’s useful to build paperclips. But there are many other things that we wouldn’t want to sacrifice to build more paperclips.

The AI alignment problem is hard to solve in part because it’s hard to specify all of our values. None of the leading ethical theories—consequentialism, deontology, contractualism—seem to capture all of our moral intuitions. And even if we were confident that one of these theories was right, it might not generate prescriptions that are clear and exhaustive enough for an AI to follow. So if we develop a powerful AI, we may not be able to fully specify its goals or the constraints under which it should operate. We may need to be vigilant to prevent subtly misaligned AIs from causing harm.

I think the AI alignment problem is important. But in this post, I won’t try to grapple with it. Instead, I want to argue that the AI alignment problem is just a special case of the larger alignment problem built into the structure of capitalism.

Windshield Wipers

In 1989, a professor from the United States took a trip to the Soviet Union and wrote a report for The New York Times. He started with this observation:

“Travelers driving through the Soviet Union can easily distinguish foreign tourists' cars from those of Soviet citizens. The latter don't have windshield wipers. The former do—but not for long.”[2]

Wiper blades, he explained, were often stolen. And once stolen, they were hard to replace. Why?

In the Soviet economy, production was organized by politics. Central planners had to decide which goods would be produced, how many would be produced, and what resources would be allocated to producing them.

In theory, one advantage of organizing production this way is value alignment. The planners could prioritize the production of the material goods that they believed were most important for human wellbeing. This is roughly the idea captured in the second half of Marx’s slogan: “to each according to their needs.”

But suppose that you were a government planner. How would you figure out what consumers needed? You might be able to estimate demand for big-ticket items from population statistics. You might decide, for example, that the average household needs two beds, one refrigerator, and one car. But how many of those cars’ windshield wipers would need to be replaced each year? What about brakes, headlights, and timing belts? And how would you calculate the right amount of resources to devote to producing these replacement parts at the expense of producing more bread or more jeans?

This is the socialist calculation problem. Even Trotsky understood it would be maddeningly hard to solve. He wrote: “The innumerable living participants in the economy, state and private, collective and individual, must serve notice of their needs and of their relative strength not only through the statistical determinations of plan commissions but by the direct pressure of supply and demand.”[3]

Unfortunately, Trotsky didn’t get his way. For decades, the Soviet Union tried to organize production without the direct pressure of supply and demand. And it made life miserable. The planners proved unable to reliably predict what people needed. Consumers routinely faced shortages for basic goods and had to wait in lines. The planners also struggled to police the quality of production. Consumer goods manufactured in the Soviet Union were generally inferior to goods manufactured abroad. And a massive black market emerged to satisfy demands that the planned economy wasn’t satisfying.

Centralized planning can’t be blamed for all the problems of the Soviet Union. A planned economy doesn’t require secret police and gulags. But it can be blamed for the lack of windshield wipers. It’s not that Soviet auto factories couldn’t manufacture wiper blades. The planners just didn’t have the information or incentives to provide enough blades to replace ones that broke or got stolen.

Today we don’t worry much that our windshield wipers will be stolen. There are auto parts stores that are eager to sell us replacements. The managers who run these auto parts stores aren’t more benevolent or more clairvoyant than Soviet planners. But they don’t have to be.

In a market economy, production is organized by profit. We don’t task any person or institution with deciding what consumers need. Instead, we have agreed on a set of rules that facilitate decentralized production. We protect private property, so people can use the resources they own as they see fit. We enforce contracts, so we can specialize and realize gains from trade. We allow general incorporation, so anyone can start a business. We permit open entry, so businesses can move into new markets and introduce new products. And we make it easy to raise capital, so companies can undertake projects that won’t pay off for years.

There are, of course, exceptions to each of these rules. Property can be taken by eminent domain. A contract to sell narcotics won’t be enforced. Entrepreneurs who want to incorporate a bank need a government charter. Businesses that want to start selling electricity or airplanes need regulatory approval. And companies that want to raise capital from retail investors need to disclose certain information to the public. But for the most part, if you identify an opportunity to profit, you can take it.

Decentralized production works because prices solve the calculation problem. As Hayek explained, the information that society needs to organize production is dispersed across the population.[4] Individual consumers know best what they need and want at any given moment. In a market economy, consumers reveal what they want by the prices they are willing to pay when they make purchases. Businesses use the information about aggregate consumer preferences that prices convey to guide their production decisions.

This way of organizing production has important advantages. A market economy can adapt to change quickly. Businesses aren’t beholden to a Five-Year Plan. If a streak of unexpectedly bad weather causes more wiper blades to break, consumers will buy more replacement blades, and prices will rise. Auto parts companies will respond by manufacturing more blades. A market economy also isn’t dependent on a small number of fallible decisionmakers. If an incumbent business—or even a whole industry—isn’t satisfying consumers, an entrepreneur can start a new company and compete with the incumbents.[5]

In the long run, the most important advantage of a market economy is its effect on innovation. Governments play a critical role in innovation by funding basic research. Indeed, the Soviets excelled at math and science—they made important discoveries we are still building on today.[6] But science itself doesn’t raise living standards. New technologies must be turned into products. And that process is too risky for many government officials. Ask yourself whether you heard more about the Obama administration’s failed investment in Solyndra or its successful investment in Tesla.

In a market economy, venture capitalists will fund the commercialization of new technologies. VCs are willing to make high-risk bets on startups because when they pay off, they can generate exponential returns. And some of those bets deliver socially valuable technologies. That’s how we got search engines, mRNA vaccines, and AI.

So there is a lot to be said for an economy that lets consumers’ willingness to pay—communicated through prices—guide production. Part of the appeal of capitalism is that its default rules aren’t paternalistic. Consumers decide what they want themselves. But we should never forget that consumer willingness to pay is not quite the same thing as human flourishing. One of the problems of capitalism is that they are subtly misaligned.

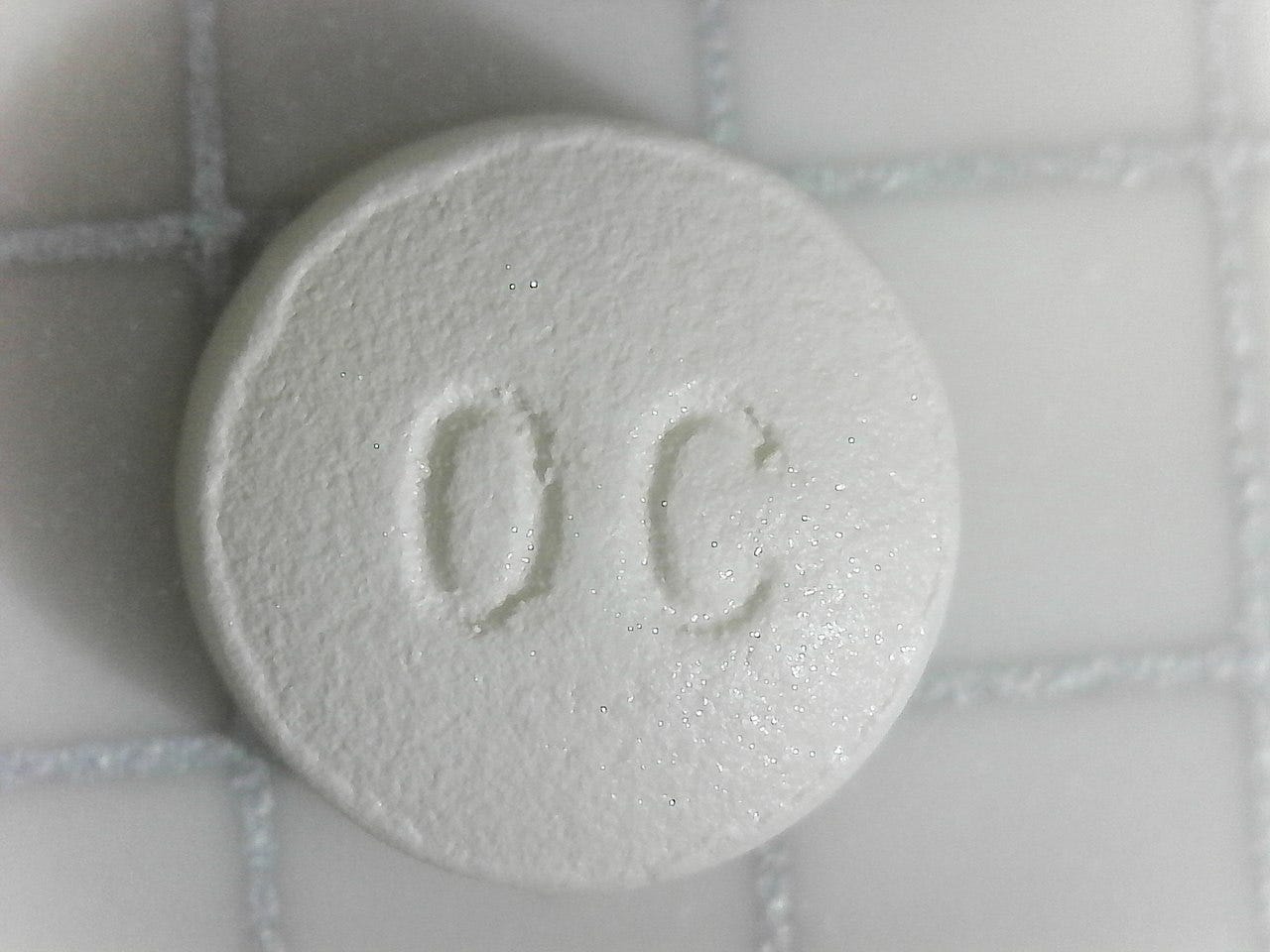

OxyContin

OxyContin is the brand name for oxycodone, a powerful opioid. In the 1990s, Purdue Pharma convinced the FDA to approve OxyContin for use as a pain medication. Purdue aggressively marketed the drug by downplaying its potential for addiction. And the company kept promoting the drug despite increasing evidence that it was addictive. Over the next two decades, hundreds of thousands of people in the United States died from opioid overdose.

Purdue and some of its executives plead guilty to crimes. The company is now bankrupt. In March, Purdue and its wealthy owners—the Sackler family—agreed to a new settlement in which they will pay around $7 billion. It’s easy to see this story as a group of rich villains committing crimes in an otherwise healthy society.

But it wouldn’t have been possible for Purdue to cause this much harm alone. They needed doctors who were willing to prescribe the drug despite the mounting evidence of its risks. They needed pharmacies that were willing to fill those prescriptions even when the same patients came back for years. And they even needed McKinsey, arguably the country’s most prestigious management consulting firm, to develop the marketing campaign. It was McKinsey consultants who proposed that Purdue could improve sales of OxyContin by paying distributors a rebate every time a patient overdosed on a drug they sold.[7]

Many actors worked together to make the opioid crisis as deadly as it was. But they didn’t need to join a grand conspiracy. They just all had parallel incentives to sell a product that consumers were willing to pay for. The same market mechanisms that help organize the production of windshield wipers can organize the production of opioid addiction. Consumers’ willingness to pay, in this case, wasn’t aligned with broadly accepted social values.

It's not that we don’t realize the risks of misalignment. In fact, we are so wary of the risks of pharmaceuticals that businesses can only bring drugs to market after they persuade regulators—based on clinical data—that the drugs are safe and effective. But even well-crafted regulation can’t always overcome the power of market forces. When the primary FDA official responsible for the approval of OxyContin left the agency, he started working for Purdue.[8]

The rise of AI may make the misalignment between corporate goals and social values more consequential. Until recently, businesses have had to rely on warm-blooded human beings to set policies and implement them. In some cases, their consciences have served as a check on misalignment. But what happens when an AI replaces some of those people?

I’d rather live in a society with an alignment problem than a calculation problem. Market economies have a better track record of protecting political freedom and improving material conditions than planned economies. But when we make public policy, we should remember that we are operating within a fundamentally misaligned system. Capitalism is like an AI—useful but hard to control and dangerous.

[1] https://nickbostrom.com/ethics/ai.

[2] https://www.nytimes.com/1989/08/27/travel/behind-the-wheel-in-the-soviet-union.html.

[3] https://www.marxists.org/archive/trotsky/1932/10/sovecon.htm

[4] https://statisticaleconomics.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/the_use_of_knowledge_in_society_-_hayek.pdf.

[5] As Coase pointed out, much economic activity is organized by firms rather than by markets in part because there are benefits to central planning. So, put differently, the advantage of a market economy is that it allows competition among multiple central planners, whose decisions are guided by prices. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1468-0335.1937.tb00002.x.

[6] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Science_and_technology_in_the_Soviet_Union.

[7] https://www.nytimes.com/2020/11/27/business/mckinsey-purdue-oxycontin-opioids.html.

[8] https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2017/10/30/the-family-that-built-an-empire-of-pain.

I'm sure in the future we'll find stuff to disagree about, but here I'm totally on board.

Lots of policies, I think, are fruitfully viewed through the lens of trying to better align the profit motive with the social good. The law and economics tradition basically takes this attitude towards law writ large. Pigouvian taxes and subsidies are one obvious example--because we think there are significant extra social benefits from installing solar panels beyond the benefits to homeowners of the energy they get, we subsidize solar panels. Another is tort law, where it's common to see the point as forcing people to internalize the social costs of their actions, so that it's unprofitable to cause harm.

While I admit there are perspectives from which this seems alien--it's a lot more natural to someone with a broadly consequentialist bent of mind than a deontological one--it strikes me as pretty attractive. I guess to the extent that I want to qualify it, it's for broadly public choice, non-ideal-theory reasons. There are lots of cases where the profit motive isn't *perfectly* aligned with social good. In principle, externalities are ubiquitous, as no transaction only affects the parties transacting. (And even setting aside externalities, individuals aren't perfect judges of their own good, as pageturner notes above.) But that doesn't mean I think government should try to price all those externalities. The perfect shouldn't be the enemy of the good, and given the realities of politics, absent a reasonably strong default *against* intervening in the market, I think what we'd likely actually get would be too close to central planning, with all its faults. While I generally want to avoid getting too topical here, tariffs are probably a good case in point. You can find pretty plausible, economically defensible rationales for this or that limited use of tariffs. (e.g., national security, or as part of some narrow, targeted industrial policy.) But when tariffs are a tool of real-world politicians, they tend to get used well beyond their defensible economic justifications, and we'd probably be better off with a strong norm against using them at all. So while I'm happy with some uses of targeted taxes and subsidies aimed at bringing the profit motive better into alignment with the social good, the general style of argument makes me uneasy, as I think it's often applied far beyond its rightful bounds.

I agree that misalignment plays some role in the explanation of the opioid crisis. But I am surprised by your claim that corporate values and behavior are misaligned with social or consumer values. Aren't you locating the misalignment in the wrong place? Misalignment is a defect of a system, a fault. But capitalism was not functioning in an unusual or aberrant way in the opioid crisis. The system efficiently and vigorously satisfied consumers' revealed preferences, as it is designed to do.

The more fundamental problem is that consumer desires are often misaligned with their objective interests, their good, and their flourishing. Once you recognize that there is misalignment at the level of the individual, phenomena like the opioid crisis follow immediately, as does your admonition about the danger of capitalism. The problem is that capitalism is just as good at supplying people what they shouldn't have as it is at supplying them with what they really need. The opioid crisis reached the magnitude it did because the supply-side systems were, if anything, too well aligned with consumer preferences, and too well-suited to the task assigned them.